“This book is not about heroes. English poetry is not yet fit to speak of them.”

Wilfred Owen

An essay exploring the poem “Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen.

By Axel Trujillo Ledesma.

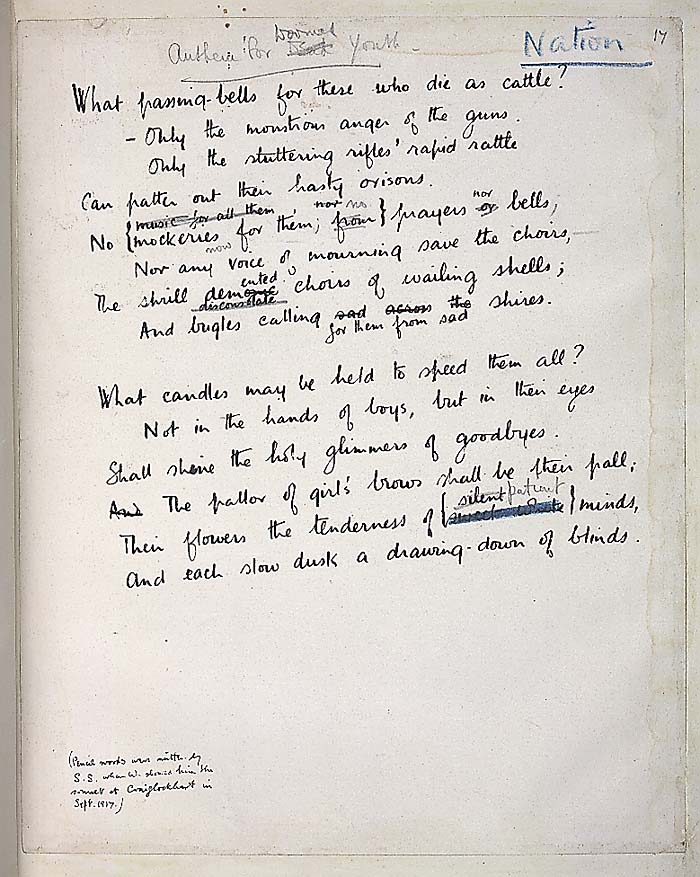

First item. “Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owens, in his handwriting!

Second item. Portrait of Wilfred Owens.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Own is a war poem that laments the deaths of soldiers during the Great War.

But it is also an elegy for the loss of the metaphysical nature of poetry.

This can be seen by analyzing the rejection of elements of traditional poetry that occur throughout the poem.

Let me explain 👇

Wilfred Owen’s “Anthem for Doomed Youth” talks about the loss of the metaphysical aspects of life. Like soldiers realizing war was not a glorious campaign.

The poem talks about the loss of metaphysical aspects in poetry.

The main goal of the poem is not to be a lament about the loss of human life but of the loss of poetry itself.

By the time the poem was written, the romantic tradition of poetry had lost its meaning.

Romantic poetry was becoming “effete”, meaning that it was losing its special quality or virtue, poetry had become exhausted and worn out (Welland, 13).

It is important to clarify that the Great War was not the cause of a radical shift in poetic tradition, however it;

“provided many writers with a new kind of material which they utilised with varying success during the war and more effectively when the passage of time had set it in perspective: the late 1920’s and early 1930’s produced the best memoirs and novels about the war but these works are more important for the newness of their content than for any radical change in their literary form.”

(Welland, 12)

Let me talk about the imagist movement, which sought out to revitalize poetry before “War poetry” as we know it existed.

Before the Great War ended the “weald of youth”, poetry was already in a debilitated condition and it was treated as ephemeral trivia (Welland, 15).

Many poets avoided writing about the war, like Yeats who answered when asked to write a War poem with:

“I think it better that in times like these A poet’s mouth be silent, for in truth we have no gift to set a statesman right.”

(Welland, 12).

It is not that nobody wrote about war before.

It is not that nobody portrayed the less glorious aspects of war.

For example in 1854, William Arnold wrote a novel called “Oaksfield” which recorded his first-hand impressions of the less glorious aspects of the frontier campaigns.

Kipling became famous for “The absent-minded beggar” with a public that conveniently overlooked his presentation of the less creditable side of war.

So, as much as there were portrayals of war that didn’t glorify it, there were cases that fell on the opposite extreme.

Tennyson’s “The charge of the light brigade” turns a massive loss of life into a “glorification of English valour and prowess”. (Welland, 15) Yikes.

Poetry in the early stages of the war is commonly referred to as bardic.

But, it is different from the true war-poetry to which Wilfred Owen is a part of.

War poetry and bardic poetry about the war are of a totally different nature.

Bardic poetry can be defined as “Self-righteousness and a stiff upper lip (which) draw(s) strength from a confident reliance upon divine approval.”

Despite writing about something new and impactful, it was still written in the same vein as the dated and boring romantic tradition that was despised by modern poets.

It was still rooted in tradition and reflected the inadequate conception of the true nature of modern warfare.

Even the horrors of war were used to fuel a British nationalist frenzy and didn’t convey the human suffering as in the poem “The Bodley Head” by John Lane.

Wilfred Owen’s writing is full of a more sensitive awareness to share in total honesty the experience of war.

The fact that he managed to transmute the feelings of being in a war and not at war into poetry is what separates him from the traditional poets.

It is not the content of his poems but the style with which he writes (Welland, 17).

The fact that bardic poetry deals with war is incidental but for poets like Wilfred Owen it is integral. Some of the poems don’t deal with war but instead with homesickness and they “invest death with an alien and heroic glamour”.

Wilfred Owen depicts a more mature vision and a fuller experience of the nature of war (Welland, 20).

What makes Wilfred Owen’s poetry different from Bardic poetry, is not only in the contents of the poems but also the perspective and the purpose of his poetry. (White, 56)

His poem reflects the changes the world was experiencing as the traditions of romantic poetry and bardic poetry were unable to render war and human suffering in the way he considered to be the correct way.

With his poem; Wilfred Owen doesn’t embellish war. Instead, Wilfred Owen’s goal is to warn others of the horrors of war.

He reveals how people are not prepared to face the consequences of this new type of war “What passing-bells for these who die as cattle?” (Owen, 1), the old ways of poetry cannot do justice to the men who die other than to make the same noise it has been doing for years.

For Owen, if war is not described as it is, in its full destructive nature then poetry is as good as dead.

Maybe in a more heroic poem or in a more heroic war, the line “Only the monstrous anger of the guns” (Owen, 2) would read as “Only the monstrous anger of the Gods” implying that there is a purpose behind the war as the Bardic poetry indicated during the early stages of the war.

But Owen’s poem aims to depict how there are really no Gods playing around with humanity’s destiny, his poetry was written “to tell the truth about modern war, as it had not been told before: to warn England and the world of what men were doing to one another” (White, 56).

Look at it like this:

There is no God.

Religion has failed humanity.

And now poetry was reduced to a form of propaganda that supported the war effort and lead thousands of men to their deaths.

Poetry, the highest of all literary forms, had failed.

Wilfred Owen exposes the inadequacy of the traditional noble and poetic forms of depicting war by imbuing the poem with the reality of death.

“No mockeries now for them; no prayers nor bells”

The antiquated form of poetry that embellishes war will not do justice to the men who die in the trenches. The safe and patriotic poetry which deliberately mocks war and the enemy is not the poetry that soldiers deserve.

It is not the form of noble poetry that humans deserve. (White, 57).

The safe structure of British poetry was ill prepared to honor the soldiers who are destroyed by “the anger of the guns”, because; what good are rhymes for a man who is bombarded day and night if he cannot hear them because they are drowned by the “stuttering rifles’ rapid rattle” (Owen, 3)?

For a poem that delves specifically into war, Wilfred Owen’s poem doesn’t portray war directly. “Anthem from doomed youth” moves away from the facts of outer experience to interpretation (White, 57).

Instead of focusing explicitly on the battlefield, the poem heavily features imagery of the church and belittles it not because the church and religion is the problem but because “prayers”, “bells” and “choirs” are reminiscent of traditions.

The poem is critiquing poetic tradition; therefore, it is only fitting that it incorporates religious elements that allude to traditional ceremonies of remembrance.

The poem compares the sound of guns, rifles and explosions to the sounds of peace found in a church because it aims to expose the inadequacies of what those symbols represent, which is poetic tradition.

Poems that glorify war imply that the suffering is in the service of a divine goal when in reality it is senseless. The prayers of old, “orisons”, are met with rifles (Owen, 3-4).

The poem asks, “What candles may be held to speed them all?” (Owen, 9) without mentioning the dead because its goal is to draw attention away from the event itself, which is war, and steer it towards the true meaning of war. “His images burst into symbols before our eyes, and we feel, not the harshness of individual suffering, so much as the tragedy of universal pain” (White, 57).

Wilfred Owen’s poem is not just about depicting war correctly, but also the emotion of war.

The second stanza does not feature any aspect of the war and still it conveys the effects caused and felt by those who are not part of it.

The second stanza tries to answer how the war will be remembered after the poetic traditions had failed to properly portray it, “Not in the hands of boys, but in their eyes/ Shall shine the holy glimmers of goodbyes.” (Owen, 10-11)

It implies that it is not the war which will be remembered and those who fought in it, but it will be the emotions that were born out of it.

The memory of the war will live in the mundane, in the “eyes”, in “flowers”, in the “drawing-down of blinds” because the noble tradition of heroic poetry failed.

The objects that represent tradition are replaced by objects that are more human or things that are not eternal and safe from the passing of time but are instead ephemeral and alive.

The war will not be remembered by hollow symbols like “bells” but by living things like “flowers”, it is not that poetry needed to be realistic but instead it needed to be based on reality.

The Great War brought a huge dose of reality with it.

The fact that “Only the monstrous anger of the guns” could have read as “Only the monstrous anger of the Gods” serves not only to indicate that there is no God toying with humanity.

But, it also indicates a loss of the metaphysical nature of poetry. Wilfred Owen prevents any further abstraction of the thought of death.

He prevents death from being cloaked by metaphor and language.

The poem by Wilfred Owen denies the involvement of a divine authority that would embellish the slaughter like traditional poetry would through pleasant rhymes and “symbolic abstractions” that have lost their meaning because the use of them would be “criminally misleading” (Lane, 128).

There is nothing beautiful of referring to soldiers as “these”, just like it is not the anger of the Gods, the soldiers are no longer the fallen or the brave, they are simply reduced to “these” because it would be inadequate to properly portray their suffering through the use of traditional poetry.

Wilfred Owen’s poem denies the value of “candles” which represent the metaphors used in traditional poetry and replaces the objects of adoration with human beings. (Lane, 128).

At the end, the poem has presented an answer to its opening line. Through the deconstruction of useless metaphor, it “searches for a suitable response to the fact of brutalized death” (Lane, 130).

It is not that the war caused a loss of the metaphysical nature of poetry.

It was integral in pushing poets like Wilfred Owen to realize how inadequate and ill-suited it really was.

It wasn’t just that traditional poetry was considered to be old fashioned, but the Great War was the perfect environment from which to draw inspiration and allowed poets to expand the capabilities of poetry by exposing its limits and flaws.

The last four lines of the poem are four different images and these images are taken directly from human experience.

They are rendered directly from sensations and not from “a stock of analogues.” They are snapshots of existence that replace the old and overused conventions of traditional poetry.

The last four lines “are images that represent reality” and not metaphors, the result of using reality to remember and honor the dead of the war creates “immediacy” (Lane, 131).

By the end of the poem, human experience is transmuted into art and the resulting poetry is the adequate response that the poem seeks.

It is possible to call Owen a myth destroyer given his rejection of the traditional poetic form, but it is also possible to see in his poem the transformation of heroism abstracted into social myth to that of heroism observed (Lane, 172).

Wilfred Owen’s poem is a response to modern warfare and a warning about how old myths, “whether cynically mishandled or simply misunderstood” were leading man to senseless slaughter.

It was the misconception about what war truly is that drove young men to enlist themselves. It was the misrepresentation of war or the lack of understanding of modern warfare which led to people believe the lie that war would be over by Christmas.

The poem by Wilfred Owen is a response to the faults and limitations of traditional poetry but also to the fact that warfare “in its technical sophistication, was more of a threat to human values than war had ever been before” (Lane, 175).

It was not the Great War that caused a change in poetry, it certainly destroyed any illusion that war is glorious or just a game.

The war did not kill traditional poetry, that had already happened before any shots were fired.

Although there were some poets like the Imagists who realized how antiquated poetry really was, it was the war and Wilfred Owen’s poetry that shed the biggest light on poetry; revealing how outdated its traditions were.

“Anthem for Doomed Youth” by Wilfred Owen uses the war to confront the old traditions and bring forward a new understanding between war and poetry.

It is not that Owen single-handedly revitalized poetry and reinvented the whole medium with a single poem, because despite confronting poetic tradition in the opening lines, the poem ends in a kind of hopeful tone.

It starts with death, but it ends with life. It is rejecting the traditions but not entirely.

It is as if the poem is not only a lament for the loss of life and poetry, but it is also a sort of wishful thinking or exhortation to infuse poetry with life instead of dead traditions.

Thank you for reading!