Over the past few years, we have seen a shift in the reception and recognition of animated media in the Western World. Animated TV shows and movies are becoming increasingly more mature and audiences now expect a higher standard of quality from animation studios. Quality that is often exclusively reserved for “live-action” movies (Lamarre, 332). But there is one studio that is often regarded as the exemplar producer of animated films. Studio Ghibli.

Animated Magic: Exploring the World of Studio Ghibli and its Creators

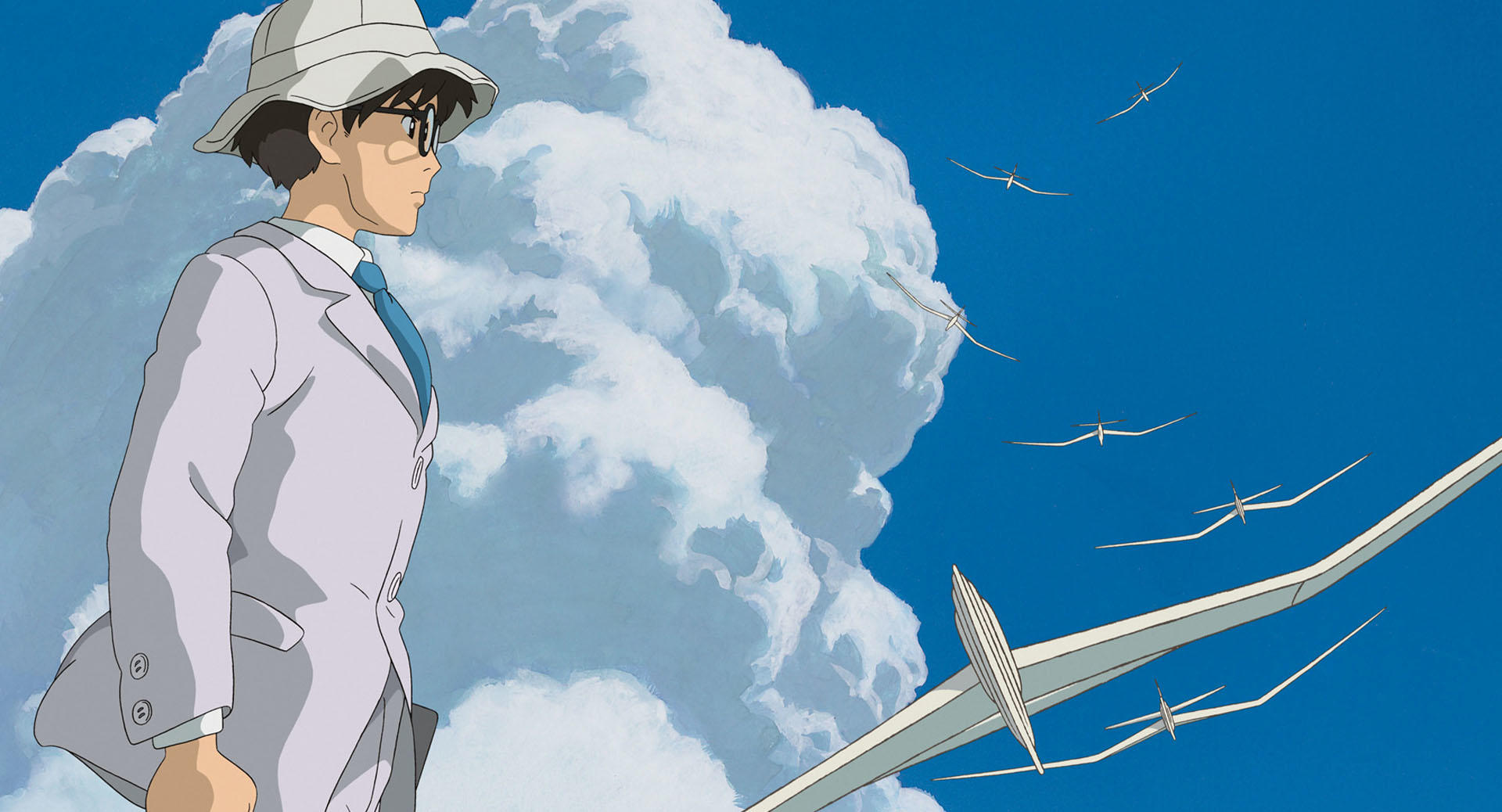

Founded by Isao Takahata, Hayao Miyazaki and Toshio Suzuki in 1985 (Herrera, 10:20), the studio is widely held as one of the most influential and important animation studios of all time, their work is often compared to those of Disney, Shigeru Miyamoto and J.R.R Tolkien to name a few (Hickson 2020). Studio Ghibli owes this recognition in great part to the ability of their directors to produce interesting and immersive animated worlds. Throughout his career, Hayao Miyazaki, has directed and produced over 10 films for Studio Ghibli, giving each one a distinct yet unique world that emphasizes the space in which the characters inhabit, including his latest film The Wind Rises (Miyazaki 2013).

The Wind Rises (Miyazaki 2013) is an animated fictionalized drama recounting the life of airplane designer Jiro Horikoshi. The film uses a myriad of techniques (what techniques? Animation of what? The sound design of who and of what? ) to immerse its audience in its world, ranging from animation to sound design; the structure of the film relies on the sensorial maturity of the audience to understand and perceive the world presented to them as an elaboration of reality. Demonstrating the capacity of the film to use sensorial reactions to not only tell a story but to force the audience to experience the animation in full.

This essay explores how Miyazaki purposefully creates ambivalent scenery in the historical context of The Wind Rises (2013) to let the viewers experience the world through their own bodies (Weedy 2018), an experience that is only feasible due to the sensorial maturity of its audience and their individual capacity to discern the animated “reality” presented to them. Proving how animated films, is able to produce a unique meaning for its audience contrary to what Pascal Quignard argues:

“Literature and the image are incompatible… When one is readable the other is not seen. When one is visible the other is not read.”

(Groensteen, 8)

In animated media the image and the word are inseparable, and so is the body from the world.

Engineering Reality

The Wind Rises (Miyazaki 2013) depicts the economical and metropolitan hardships of Japan from the 1920s to the 1930s during the life of Jiro Horikoshi. One of the major events used to explore this period is the 1923 Great Kanto Earthquake that devastated the entire metropolitan area of that time, destroying over 300 thousand buildings and homes, killing almost 100 thousand people (Minami 2014). The film characterizes numerous elements of these events (what elements and how are they characterized? Give an example of this in the movie “Such as; Jiro’s clothes, the crowd’s reaction, etc.”) and the people that witnessed them in a fictional manner. The animators must find a way to recreate these events in a believable yet abstract way. (How do they do this?)

14 minutes into the film and Jiro meets his future wife, Nahoko. In this scene we can appreciate all of Miyazaki’s ideas and techniques employed to immerse the audience in his films. Both characters are on a train to Japan and when Jiro loses his hat to the wind passing through, Nahoko catches it and we hear the force of the wind as the animation smoothly transitions to the actions of our characters, and their dialogue.

“The wind rises…” – Nahoko says

“…, we must try to live.” Jiro responds

The Wind Rises (Miyazaki 2013)

We hear the train machinery and the waver of their clothes as they say goodbye to each other to a melancholic melody by Joe Hisaishi. The inexistent camera, or rather the framing of the illustrations, is fixed and allows the animated world to move on its own as we see the clouds and mountains passing by from the train. Jiro sits down and contemplates the scenery.

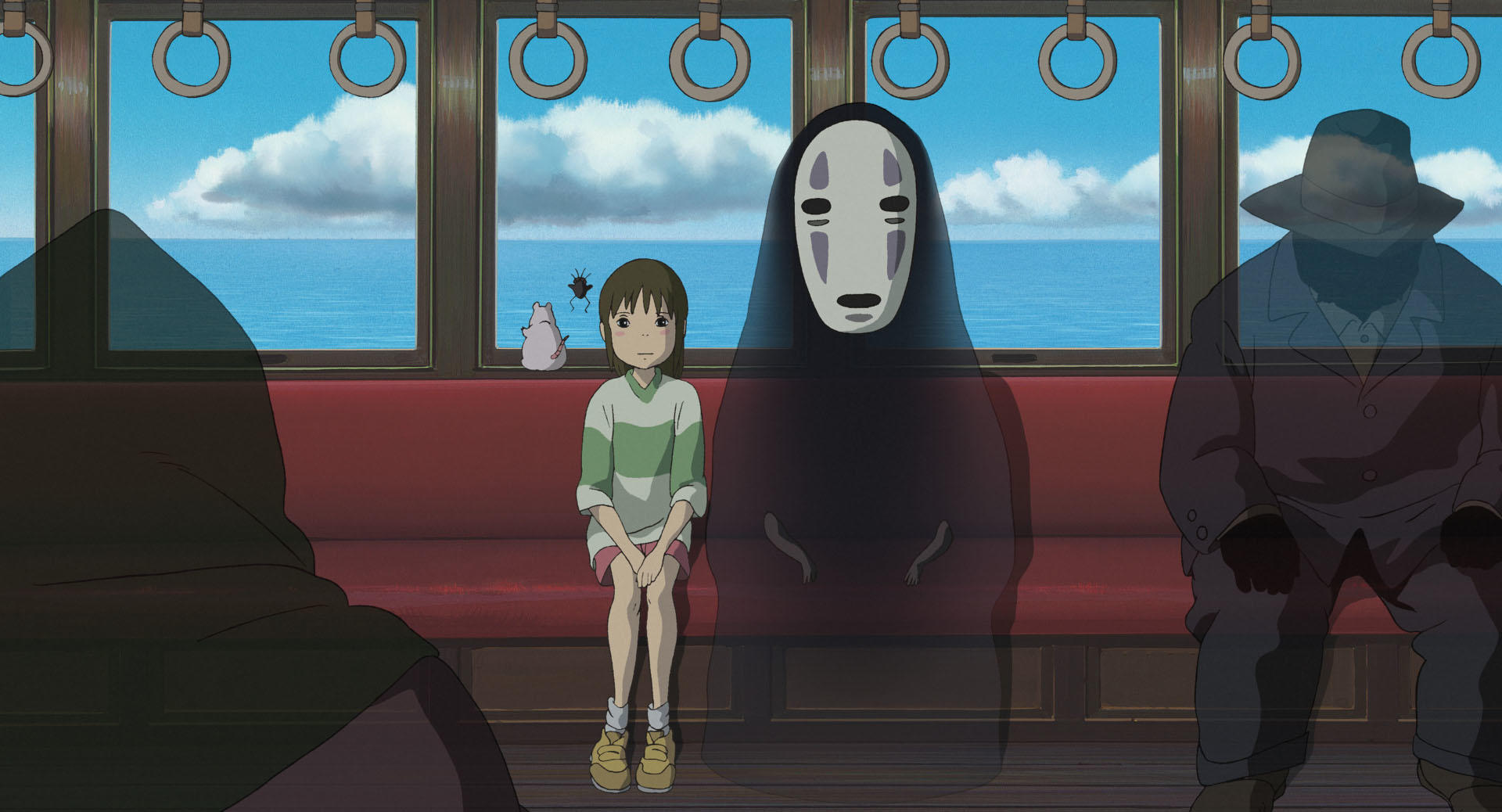

The animation plays an even greater role as it is the vehicle through which we interpret the story, or rather, the world (Weedy 2018). In her essay, “Chihiro Boards a Train: Perceptual Modulation in the Films of Studio Ghibli,” Kate Weedy describes what Miyazaki calls a “Ma” scene. A scene in which a character, often the protagonist; sits, stands or is simply still for a moment without offering any sort of progression. Eliciting a feeling from the audience that is not explicitly shown by the film (Weedy, 1).

These feelings are experienced by the audience as they watch the two-dimensional drawings come to life by combining sounds and motion that would otherwise mean nothing by themselves. The animated stillness forces the audience to keep looking as they interpret the various images and sounds and relate them to a pre-existing reality through their own body (Weedy, 1). With memory and experience the human brain can connect all these elements with the reality that forged them.

It is not whether these sequences are real, or as real as photography-based cinema is (Lamarre, 332), but how said sequences are executed for the audience to experience them as a reality.

Shortly after, a moment of silence passes before Japan is devastated by an earthquake. Firstly, the entire devastation sequence occurs without any music and solely relies on dialogue and sound effects. The frame cuts to a whisper and the dark image of the ground as it cracks from beneath as if hell itself was rising to take over Japan. Then we pan out and see a shockwave coming from the nearest sea to the city. Buildings start to rise and fall with the waving of the earth and what was once a whisper has now turned into the angry rumblings of the earth. The train halts and the metal screeches as sparks and dust fall to the ground. The more buildings fall the more sounds they make. These sound effects are produced by the recordings of human sounds such as hissing, screeching and grumblings. As Jiro, Nahoko and Kino run through the falling city, they hear more rumbling and more screeching produced by human voices. What sounds like screaming is the fire spreading, what sounds like thumping are the buildings falling.

This approach allows Miyazaki to put a more personal touch to the film and emphasizes the world as a character on ways traditional sound editing would not allow. The film often prioritizes these recordings of human sounds over dialogue and background characters, forcing the audience to immerse themselves in the world created by the film.

The sensorial maturity is what allows the film to exist in the first place for both the creator and the spectator. Miyazaki and his team borrow from reality and transform it how they see fit through animation. The details, development and flow of every aspect of the film can only stem from the author’s understanding of the real world and how they decide to represent it. By enhancing the animation and adding to the film as much detail as possible, while still adhering to budget, time and most importantly, the interest of the audience, Miyazaki states:

“My films show the world’s beauty. Beauty otherwise unnoticed. That’s what I want to see.”

Never-Ending Man: Hayao Miyazaki (2016)

Whether it be small, calm moments or fast-paced action scenes, the world and its characters must carry the same level of realism, or rather, the illusion of the same level of realism. Allowing the audience to sense the two-dimensional frames and perceive them as real. The way the film fulfils this illusion is by paying attention to the details beyond the story. The sounds you never hear, the movement you never see. Animation is forced to pay attention and recreate what is taken for granted in western photography-based cinema because in animation everything is made from scratch.

In her article What Is Body, What Is Space? Performance and the Cinematic Body in a Non-Anthropocentric Cinema (2016), Anne Rutherford talks about how different media allows for a deeper understanding and depiction of the body than traditional photography-based cinema. With new or alternative forms of cinema such as animation, or digital cameras, authors are granted more tools of presentation and are forced to consider what can or cannot be achieved.

“What the western tradition sees as empty space is just as full as the point where the mark of the pen hits the page.”

(Rutherford, 8)

Rutherford describes how the figure of the image is the body, the ground and the space in which they exist (Rutherford, 4). All elements are considered and designed specifically to illustrate reality. Even in a completely digital media *someone* must consider *something* before an image is created. As human beings we are forced to recall thoughts or experiences to interpret reality, and both the audience and the production team render reality as it develops in front of them. Movies are seen and heard and felt. Instead of appreciating movies in a mere cognitive level, Miyazaki demands sensorial maturity.

Sources

Pons, Mellissa. “The Wind Rises Sound Design Analysis – Intro.” The Sound Design Process, 17 Apr. 2017, thesounddesignprocess.wordpress.com/2017/04/17/the-wind-rises-sound-design-analysis-intro/.

Pons, Mellissa. “The Wind Rises Sound Design Analysis I: The Oneiric Realm of Jiro (Part 1).” The Sound Design Process, 24 Apr. 2017, thesounddesignprocess.wordpress.com/2017/04/24/the-wind-rises-sound-design-analysis-i-the-oneiric-realm-of-jiro-part-1/.

The Wind Rises.” Directed by Hayao Miyazaki, performance by Hideaki Anno, Miori Takimoto, Hidetoshi Nishijima, and Masahiko Nishimura, Studio Ghibli, 2013.

Only Yesterday.” Directed by Isao Takahata, performance by Miki Imai, Toshirô Yanagiba, Youko Honna, and Daisy Ridley, Studio Ghibli, 1991.

Anime: How Japanese animation has taken the West by storm,26 March 2022, Becky Padington & Ian Youngs, BBC NEWS

Groensteen, Thierry. “Why are comics still in search of cultural legitimization?” A Comics Studies Reader, edited by Jett Heer and Kent Worcester, University Press of Mississippi Jackson, 2009, pp. <3-11>.

Barnett, David. “Studio Ghibli: An indispensable guide.” BBC Culture, 23 Jan. 2020, https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20200123-studio-ghibli-an-indispensable-guide

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.