Where does a film begin? During pre-production, or after a final cut of the film is completed. What constitutes as the materiality of a film, and what does a film actually do?

In film animation, the use of various media and techniques creates a manufactured reality that is designed to engage our senses and emotions in a way that feels real to ultimately create a simulation of reality. In the film, Ghost in the Shell (1998) the integration of human consciousness with AI technology blurs the lines between what is real and what is simulated, as the cyborg characters navigate a world where technology has transformed the very nature of consciousness and embodiment. The link between AI and film as a simulation of manufactured reality, is that both involve the creation of a constructed product or system that is designed to replicate, imitate, or even surpass the complexity of human experience. By exploring the process of how the film was made and the various technologies and techniques used to create it, Ghost in the Shell (1998) offers an insightful lens through which we can understand the hyperreality of films, a concept introduced by French philosopher Jean Baudrillard.

We will analyze Ghost in the Shell (1998) through Ina Bloom’s text, The Autobiography of Video: Outline for a Revisionist Account of Early Video Art (2013, 217-424), by using her approach of writing a biography of a technological object and explore how the creation of the film is itself a simulation, with layers of simulated reality and hyperreality.

Contextualizing the film, “Ghost in the shell” and the subject

Ghost in the Shell (1998) is a mix of science fiction and cyberpunk anime film directed by Mamoru Oshii, based on a manga series of the same name by Masamune Shirow. The film is set in a futuristic world where humans and machines have merged, giving rise to cyborgs and artificial intelligence. The film’s central themes explore the relationship between humans and machines, with an emphasis on how AI simulates the human experience. Ghost in the Shell (1998) offers a unique case study to explore the idea that films are a simulation of reality because the film raises profound questions about the nature of reality, identity, and perception, which are all central to the idea of simulation. Additionally, the film’s stunning visuals and intricate world-building rely heavily on various technologies and techniques, such as hand-drawn animation, photography and painting, to create a fully immersive realized fictional world. (Shin 2011, 8)

One of the key influences on the cyberpunk genre and Ghost in the Shell (1998) is the work of Jean Baudrillard, particularly his book Simulacra and Simulation (1994). Baudrillard argues that we live in a world of hyperreality, where simulations and representations have replaced actual reality. Baudrillard presents a bleak picture of a world in which everything has become a simulation and there is no longer any authentic or meaningful reality to be found. In this sense, the film can be seen as exploring the idea that the human experience is increasingly simulated. However, in film the audience is immersed in this hyperreal world, which is often designed to elicit certain emotional responses or to convey a particular message or idea. In this way, film creates a simulation of reality that is both manufactured and hyperreal. (Baudrillard 1994)

In her essay, The Autobiography of Video: Outline for a Revisionist Account of Early Video Art, Ina Bloom suggests that to trace the lifespan of video technology is to attempt to write the biography of a technological object, essentially simulating the life of an object which involves tracing the changes in the object and the changes it effectuates. Bloom’s ideas of technological objects and simulations can also provide a framework for understanding the origin of the film. In this context, the origin of a film can be seen as a simulation that takes place throughout the process of filmmaking. The idea for a film may be the first stage of this simulation, but it continues throughout pre-production, production, and post-production. Each stage involves the use of technological objects, from cameras and lighting equipment to editing software and special effects, that contribute to the hyperreality of the finished film. (Bloom 2013, 286)

Hyperreality of animated films though materiality

The materiality of Ghost in the Shell (1998) is defined by the collaborative efforts across different medias and works. In an article published for the Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock (2022), the authors argue that film is a form of simulated reality that relies on various technologies and techniques similar to those used in medical simulations to replicate specific scenarios influenced by real human experiences. Filmmaking, in general, is achieved using advanced technologies and techniques that blend different media together to create a seamless, immersive experiences for an audience. This process involves the integration of digital effects, sound design, music, cinematography, and editing, among other things, all of which are designed to simulate the experience of being in a particular place and time, with a particular set of characters and circumstances. (Lateef 2022, 3-4)

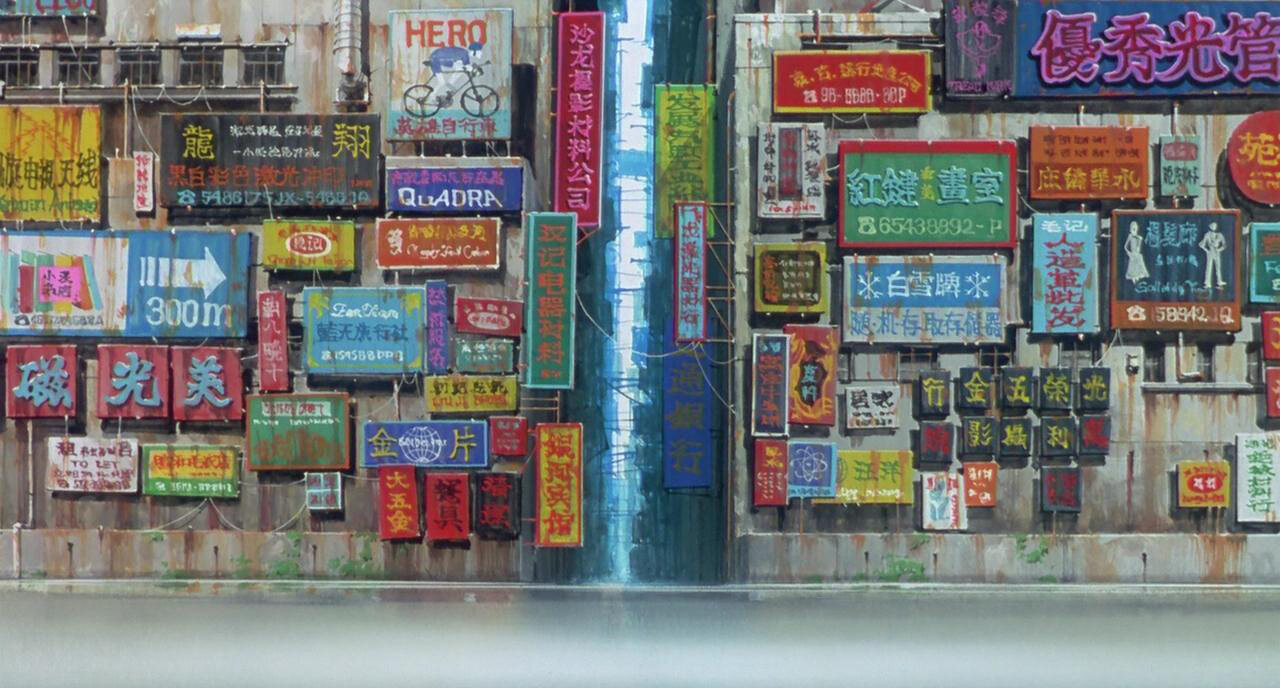

During the production of Ghost in the Shell (1998), the background paintings, as seen in figure 2, were created based on real-life locations that required a scouting phase in various areas of Japan. These paintings aimed to capture the realistic nature of the locations while also being stylized to fit the director’s vision for the film. (Lum 2018) While the locations themselves were real, the paintings became a simulated reality that only existed within the film’s world. Even though these painted locations never actually existed, the audience can still recognize and relate to them as part of the film’s world.

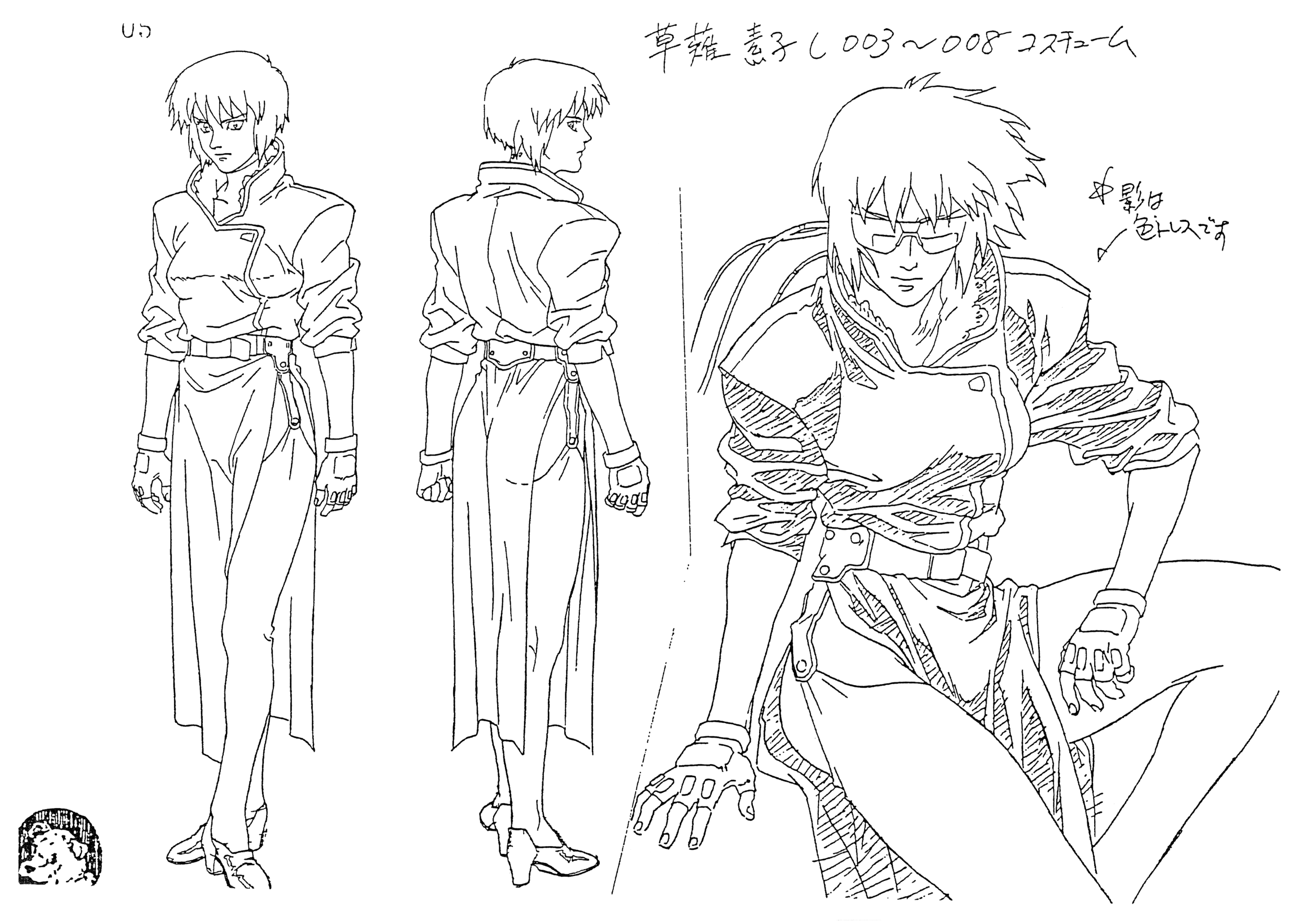

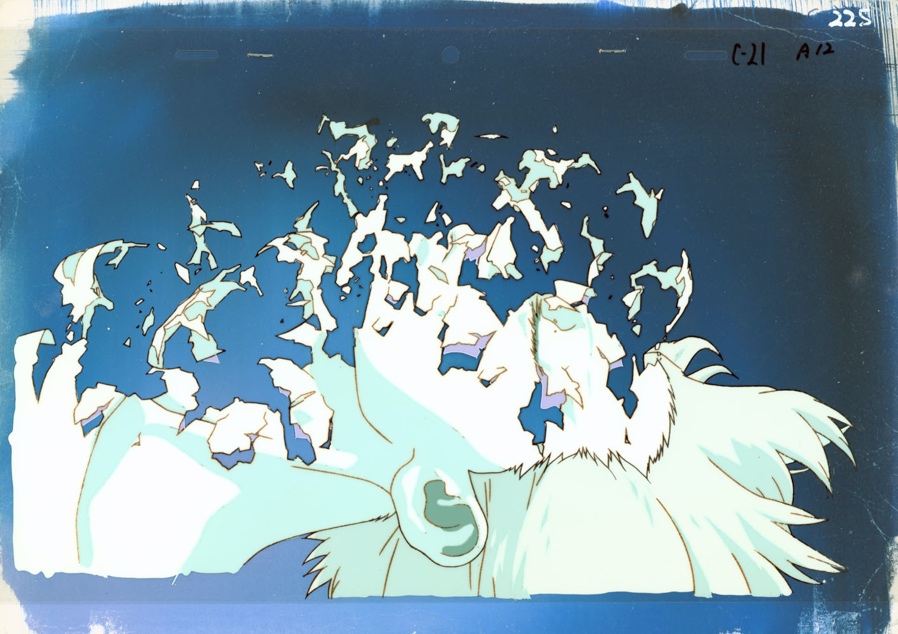

The characters and objects are then drawn on separate transparent celluloid sheets called “cels” as seen in figure 3. This technique allows for different parts of the animation to be moved independently of the background, giving animators greater control over the motion and allowing for more complex scenes. Multiple cels are drawn and then placed on top of the painted background one at a time, giving the illusion of depth and movement. This process is time-consuming and requires a high level of skill, but it even allows animators to repurpose backgrounds and cels for different scenes (Heginbotham 2023). Figure 4 shows a screencap from the film, showcasing the final result.

It is important to note that Ghost in the Shell (1998) was allocated a particular high budget compared to different animated movies from Japan at the time, which granted the creators access to different media and the time to experiment with it. It also allowed the animators to paint and draw unique backgrounds and cels for different scenes. (Lum 2018)

The beginning stages and process of filmmaking are an integral part of the film’s materiality. Without these stages, the simulation would not exist. As Bloom’s ideas suggest, technological objects should be studied not only as finished products, but also as the result of a series of processes that shape their materiality. The materiality of a film and its contents create a medium through which the audience can experience the film. However, Ghost in the Shell (1998) and animated films in general are unique because they do not rely on recordings of real-life events, unlike live-action films, rendering a re-mediation of the simulated reality that the film is trying to depict. (Shin 2011, 20)

In an article by Hyewon Shin, she explores how the film achieves its cinematic look, designed to replicate real-life physical traits that cameras produce during filming, such as lens distortion and lens flairs. We can look at the scene in which a mind-controlled sanitation worker wakes up from a simulation he thought was his real life, in which his family does not really exist.

In Ghost in the Shell (1998), the filmmakers not only simulate a manufactured reality but also simulate the physical conditions under which such a reality could be recorded. Mimicking the limitations of the camera, the movements and expressions of the characters, and sound simulating real-world environments. The animation process allows filmmakers to exaggerate and manipulate reality, creating a highly stylized version of what is real. This stylization enables the audience to accept and engage with the story’s narrative, despite the fantastical or impossible elements depicted on screen (Shin 2011, 20) Shin describes the film’s digital re-mediation as “simulating cinema’s special and emotional depth, that does not give the audience neither an experience of modernist psychological realism nor of postmodern flattening.” (Shin 2011, 20) Meaning that animated films offer a unique simulation of the hyperreality, that is in itself a simulation, that live-action cinema offers.

The character of the construction worker is shown a picture of himself walking his dog as seen in figure 6. The use of a “fish-eye” shot in the scene creates a sense of realism by mimicking the way pictures are taken in real life. By using this technique, the animators make it easier for the audience to identify with the character and the situation, even though it is a simulated reality. This “non-real image,” as Shin puts it, “evokes the spectator’s emotional response and affective investment.” (Shin 2011, 20) The distorted perspective also emphasizes the idea that reality can be subjective and manipulated, which relates to Baudrillard’s concept of hyperreality.

By looking at figure 6 we can explain the hyperreality animation filmmaking in a practical, and yet amusing way. Consider that what we are looking at is a simulation of a man holding a picture, because neither the man nor the picture ever existed in real life. Then we have the picture itself which is a simulation of a situation that never happened or was ever recorded using a camera that never existed, because it is a drawing. All adding up to a scene of a movie that is a simulation of a series of events that were scripted and never happened. Ina Bloom’s ideas suggest that a technological object, such as a film, is not a static or fixed entity but rather a constantly evolving one that can be experienced differently over time. Therefore, a film can be analyzed as an experience or an event that can happen at multiple times, even after the initial production of the film. When we begin to consider the media though which we experience the film such as DVDs, or streaming platforms, each experience may be slightly different due to the different context of each viewing. However, none of these experiences are a lesser version of the film or the original version of the film since they all contribute to the evolution of the technological object that is the film. (Bloom 2013)

This means that the origin of the film’s contents cannot be defined as a single point in time or phase, such as pre-production, because the entire process of making a film is part of its materiality and contributes to the final simulation presented to the audience. In this sense, films are not simply a passive form of entertainment, but an active form of simulation that actively shapes our understanding of the world around us.

Bloom’s concept of the biography of a technical object can be applied to the character of Major Motoko Kusanagi. She is a product of simulation, not only in terms of her cybernetic body, but also in terms of her memories and consciousness. She struggles with questions of identity and authenticity, as her memories are not entirely her own but are artificially implanted. This ties into Bloom’s idea of the constructed self, where the self is not a fixed entity but is rather a constantly changing product of the environment and the experiences that shape it. (Shin 2011, 10)

In the film, the character Kusanagi’s ghost is represented by her voice, which is sometimes heard without her speaking. Her voice is an important part of her identity because it represents her human-like qualities and emotions (Shin 2011, 10) Shin argues that the filmmakers’ use of an artificial voice for Kusanagi disrupts the conventional methods of filmmaking and the audience’s usual expectations of how a character should sound. Despite being non-realistic, the artificial voice is designed to simulate human emotions and allow the audience to still sympathize with her character.

Earlier we looked at an article that discusses the similarities between medical simulation and filmmaking. The article highlights the practical advantages of completing such simulations, both in the context of filmmaking and medical training. The goal of the article is to examine how simulation techniques can be utilized in different fields, and how they can be used to improve the overall quality of the final product or outcome by creating effective and immersive experiences. Exploring the simulation that is filmmaking and the immersiveness of those experiences is important because it allows us to reflect on the media we consume. By examining the techniques and creative decisions behind a film’s production, we can gain insight into the motivations and intentions of the artists and filmmakers involved. This can give us a better understanding of why certain media is created and how it impacts us as viewers. Additionally, by studying these simulations, future artists and filmmakers can learn from them and improve their own craft. (Lateef 2022, 6)

Conclusion

The film Ghost in the Shell (1998) explores the relationship between humans and machines, blurring the lines between what is real and what is simulated. The film uses various technologies and techniques to create a fully immersive realized fictional world, thus creating a simulation of reality that is both manufactured and hyperreal. The film’s origin can be seen as a simulation that takes place throughout the process of filmmaking, using technological objects to contribute to the hyperreality of the finished product. Ina Bloom’s approach of writing a biography of a technological object provides a framework for understanding the materiality of the film, such as the use of hand-drawn animation, photography, and painting. Jean Baudrillard’s writing is key to understanding the concept of hyperreality, highlighting the relation between the technological object and our experiences of reality are constructed through cultural and technological practices. Films, as technological objects, contribute to this construction by creating hyperreal experiences for viewers.

Animated films do not exist or originate at a specific time or through a specific medium. Instead, it is a product of a series of technological and cultural processes that are constantly changing and evolving. Film is not just a collection of images or sounds, but a complex interplay of various elements, such as cameras, lenses, film stock, editing techniques, and distribution methods, that shape its form and meaning. Therefore, a film is not just a static object, but a dynamic and evolving entity that is shaped by various factors, including the technologies and cultural practices that are used to create it, and how an experiences those collections of simulations.

References

Oshii, Mamoru. Ghost in the Shell. Manga Entertainment, 1998, DVD.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and Simulation. University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Bloom, Ina. “The Autobiography of Video: Outline for a Revisionist Account of Early Video Art.” Critical Inquiry vol. 39, #2 (Winter 2013): 217-424. doi: 10.1086/668526

Shin, Hyewon. “Voice and Vision in Oshii Mamoru’s Ghost in the Shell: Beyond Cartesian Optics.” Animation vol. 6, #1 (March 2011): 3-75. doi: 10.1177/1746847710391506

Lateef, Fatimah, Brad Peckler, Eric Saindon, Shruti Chandra, Indrani Sardesai, Mohamed Rahman, S Krishnan, Afrah Wahid Ali, Rose Goncalves, and Sagar Galwankar. “The Art of Sim-Making: What to Learn from Film-Making.” Journal of Emergencies, Trauma, and Shock vol. 15, #1 (2022): 3–11. https://doi.org/10.4103/jets.jets_153_21.

Lum, Patrick. “Ghost in the Shell’s Urban Dreamscapes: Behind the Moody Art of the Anime Classic.” The Guardian. Last modified August 3, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2018/aug/03/ghost-in-the-shells-urban-dreamscapes-behind-the-moody-art-of-the-anime-classic

Heginbotham, Claire. “What is Cel Animation & How Does it Work?” Concept Art Empire. Last accessed April 22, 2023. https://conceptartempire.com/cel-animation/

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.